Q&A With UNCF CEO Michael Lomax: We’ve Got to Garner More Resources for Low-Income Kids for This Journey “To and Through” College

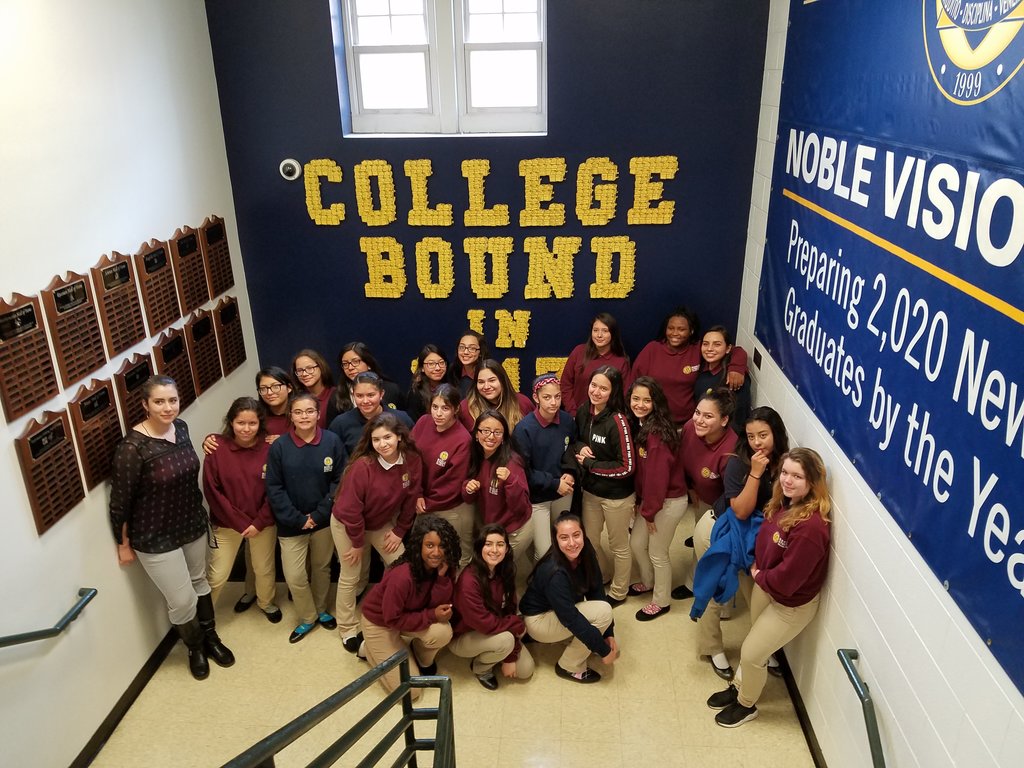

UNCF President and CEO Michael Lomax at the May 2017 UNCF Student Leadership conference with scholars from several programs, including the Walton-UNCF K-12 Education Fellowship and the Alliance Data Scholarship and Internship Program. (Photo Credit: UNCF)

Last fall, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People called for a moratorium on charter school expansion until a number of changes are made to the system, including how public charter schools are funded and how they are held accountable for performance.

The NAACP then created a task force to travel the country to survey the state of charter schools and how they are serving minority students in urban communities. The task force released its report last month, doubling down on the organization’s stance from last fall to freeze charter school expansion.

In response, more than 160 education leaders and stakeholders sent a letter to the NAACP asking the organization to reconsider its resolution. Michael Lomax, president and CEO of the United Negro College Fund, was among those who signed the letter, saying at the time that a moratorium would limit student access to quality schools, particularly for black parents who “overwhelmingly support charter schools and being able to choose the best option for their children.”

With the first-ever data from The Alumni that charter schools are seeing low-income minority students through college graduation at rates three to five times the national average, The 74 spoke with Lomax about how charter schools serve that segment of children, where the NAACP’s stance plays into that, and whether the aspiration for a college degree is a golden ticket to success for every student.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

The 74: College graduation rates for low-income, minority students pale in comparison to their affluent white peers – a mere 9 percent earn degrees within six years, compared to 77 percent of students from high-income families as of 2015. What is UNCF’s approach to tackling this problem?

Lomax: We know that the best predictor of student success is family income. And short of increasing the family income of low-income black students, we focus on providing strong support — academic and financial — that will enhance those outcomes. We see that at a number of our institutions and institutions nationally. The more financial support we’re able to give students, and the stronger the academic and social supports, the greater the prospect of graduating both on time and in larger numbers.

We see in our [historically black colleges and universities] that the institutions with the largest percentages of low-income students and least resources have lower graduation rates. The national graduation rate across all HBCUs is about 33 percent, and 70 percent of students at those institutions on average are Pell-eligible, so we’re seeing in HBCUs a three and a half to four times greater graduation rate than is to be expected of their low-income peers [in non HBCU institutions]. And they’re achieving that with fewer resources. But where they are providing more financial aid and stronger academic and social supports, the graduation rates increase. At a wealthier HBCU like Spelman [College], the graduation rate is 76 percent.

We know what to do. The question is, do we have the will and resources to do it? What needs to be done to ensure stronger graduation rates for low-income kids of color is more financial, social, and academic supports. We have more tools today than in the past. There are new analytical tools that can better identify what interventions are needed for students. We’ve got to garner more resources for low-income kids for this journey to and through college.

Where would those resources come from?

Right now we’re working very hard to ensure we don’t lose the resources we do have from the federal government. UNCF is fighting hard to preserve tools like campus-based aid, the Perkins Loan, work study, the [Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant], so low-income students have the potential resources to cover their costs. UNCF is fighting hard to ensure that there are increases in the Pell Grant, and we had some success this year, with Congress increasing Pell from being nine months to 12 months, so students have the prospect of being in school 12 months of the year and completing more rapidly.

One of the resources that UNCF and HBCUs has relied on is Title III, which is really an institutional grant made to HBCUs. The size of the grant is based on enrollment, and those funds are the working funds that HBCUs have used for 50 years to invest in programs to improve institutional performance around areas like retention and completion.

But the big problem on the federal level is we don’t have strong support from the Trump administration for these initiatives. Although promised, we’re not seeing investments made. At UNCF we’ve said we want to see the same kinds of investments made in HBCUs that we see being made in charters, to enhance and expand their reach, because we know that HBCUs are a proven institutional model just as we know high-performing charters are, but we’re not seeing a new commitment from the administration to support HBCUs as we are seeing them in charters.

The federal support in Pell grants and other grants is not keeping pace with the cost of college, so many of these students are being forced to either take on debt, which they’re increasingly averse to, or they’re working, which is an obstacle to persistence and completion.

For the foreseeable future, low-income students are going to have to rely on federal loans. But there’s a lot that we can do through better public policy to make that less onerous in terms of its impact on them. We can have universal income-based repayment, we can lower the interest rate, we can provide for forgiveness through community service. And again, those are incredibly important public policies that many of the folks at the federal level who are decision-makers who support charters are not seeing the connection between supporting charters and enhancing the K-12 opportunities for low-income kids and understanding what it’s going to take to get them college degrees. Those of us who are advocates for charters need to get federal decision-makers to make more thoughtful decisions.

The other source of support, of course, is philanthropic. That support has, over the last decade and a half, driven so much of the growth and innovation in charters. We haven’t seen equivalent investment in HBCUs and other minority-serving institutions. There’s a bigger opportunity for philanthropy beyond K-12 into ensuring the young people now graduating high school college-ready can attend HBCUs and minority-serving institutions, and ensuring that those institutions have the capabilities not only to provide financial support but also academic and social supports.

How do you respond to findings from The Alumni that some of the top charter networks are doing substantially better in terms of college success rates for their alumni, compared with traditional public schools?

I’m a big charter supporter, I serve on the KIPP board. I want to challenge the data to be as accurate as possible. I’d like to see what the college-going rates are from students from all charters, not just cherry-picked from the highest performing charters. I know what the high-performing charters are doing. I know that the KIPP network, which is of course the largest charter network, is very focused on “to and through college,” and is investing in a lot of resources that most traditional public schools — and I suspect, many independent charter schools — just don’t have in order to get the results that we have to work very hard to achieve with our students.

I think there’s a lot to learn from KIPP and our “to and through college” program — our students are graduating at a close-to 50 percent rate, but what does that take to do it? It takes a counseling program, which is very intense and very engaging with KIPPsters from middle school on. The college-going goal is established in pre-K or elementary school. The amount of work we do on college match is extraordinary and is a part of the reason why we’re seeing stronger results. KIPP is advocating for students in financial aid to get resources so that they’re not burdened heavily with debt, so they don’t have to work, so they’re getting the scholarship support that they need.

This is hard, hard, work and I think it’s due a lot of recognition and acknowledgement, but part of it is also to say, you can’t achieve these kinds of numbers in a traditional school that has a counseling operation in which there are 200 or 300 students for each counselor. They can’t give students the kinds of individual support and attention just on the counseling front alone.

Should all high schools hold themselves accountable for college success rates?

I think that we’ll have to see over time whether high-performing charters can sustain this, but they’re sending a lot of their students to some of the most heavily resourced colleges and universities where financial aid is more readily available. But when we’re sending our students to city colleges and less resourced private institutions, what are the completion rates there?

So I’m reluctant to say what we’re learning from these results is that these [charter schools] are somehow better than [traditional district schools], but they certainly have more focus and more resources to achieve. We also have to ask the question, “We’re about to have half the students at these charter schools going to college, what’s happening to the other half?” You can’t talk about these extraordinary results in completion without raising that question. What are these high-performing charters doing for students who don’t go immediately to college, or opt not to go to college. What are their employment rates? What kinds of jobs are they being prepared for?

There’s a lot to learn, a lot to be proud of, but it’s all a part of us building a better sense of what it takes. If we’re going to replicate this in traditional schools and all charter schools, then it’ll take more resources and investments.

(Editor’s note: The data reported in The Alumni only accounts for students earning four-year bachelors’ degrees. Those earning two-year associates’ degrees are not included in the data.)

What is your take on the NAACP’s latest rhetoric against charter schools?

I haven’t had an opportunity to talk with the NAACP yet, but in a democracy, you’re going to have people who have different positions. They’re a principled organization and they have a strong view here.

Let’s ask questions about what they’re saying about charters, and what can the charter movement do to address some of the concerns. I would say first of all that the charter movement is vulnerable on the issue of the quality and performance of charters writ large. The charter movement has to do more in my view to get rid of low performing charters, I think it hurts the brand. You can’t just focus on a handful of high-performing charters and say that’s the sector. The sector has low-performing charters and they are making the movement vulnerable to criticism about quality and results.

I do think that in some communities around the country you’re beginning to see charter authorizers authorizing charters that will be in some ways akin to the segregation academies of the 1960s. There will be charters that, because of where they’re located, will be restricted to whites, or to middle-income white students. There do appear, in some cases, to be authorizers sought in order to be obstacles to those students having to attend integrated traditional public schools. As long as charters become a subterfuge for that, they are going to be a subject to some level of criticism as well.

I think that the best antidote to any of the criticism from the NAACP and others is really to look at some of the communities where we see charters and traditional schools improving together, and where a student has an opportunity to get a really strong education whether she’s in a traditional school or a charter. In Washington D.C., where nearly half of the students are in charters, we’ve seen the system under Kaya Henderson innovate for traditional schools. And we see the system growing and their results strong. We see increasing improvements for the Chicago Public Schools, where, again, you have a strong charter sector but also a focus on taking some of the learnings from charters and innovating in traditional schools and improving them.

There’s recent research about the positive impact that charters are having in traditional schools in Memphis. I think that’s the story to tell. Whether that will ultimately persuade the NAACP to take a different point of view, I don’t know. But I would also say that regardless of the criticism from the NAACP — and I respect them as an institution, they do incredible work in a number of areas — the demand for high-performing charters continues to grow, and even in the communities that have been slow to expand, you’re seeing them now moving to expand, and expand thoughtfully and carefully.

One of these is in Atlanta, where charter expansion has really been at a slower pace, but even after the laws and the constitutional amendment in the elections last year, Atlanta Public Schools have entered into agreements with two national charter management organizations, including KIPP, to expand significantly. So regarding the criticism, I don’t agree with it, but I don’t think it’s proving to be an existential challenge to charters, and I do know that organizations like KIPP are disagreeing with the NAACP, but they are also working hard to build relationships with them on the local level.

Taking four to six years of money-making working time to instead spend money and accrue debt by going to college can be a tough pill to swallow. Are successful charter schools better equipped than others to inform and prepare black and minority students for the rigors and opportunities college can present?

African American parents understand that college is the gold standard — nearly 90% of the parents we’ve been tracking with our UNCF Parent research say they want their kids to go to college, and they want them to earn college degrees. These parents are working very hard to ensure that that goal is achieved. Whether they all have the kinds of knowledge and resources to drive that is another question.

The research we’ve seen from a recent Learning Heroes report is that 90 percent of low-income parents think that their kids are performing at or above grade level in English Language Arts and math, when it’s really more like a third.

Have we given parents the tools to assess their kids academically? I’d say across the board we’re not doing that, and we have to do a better job of that. A lot of this has to be done by counselors and teachers, but the most influential adults in the lives of children are their parents and family members and caregivers, and we have to do a better job across our communities in educating parents.

The college-isn’t-for-everyone mantra has been really hot lately. To what extent do you agree or disagree with it? Do the issues around that concept differ for black students versus whites and other minorities?

This is a really important consideration in the high-performing charter sector: How do we balance this articulation of “to and through college” — in which the goal for KIPPsters is to pursue college in higher numbers — with the notion that not every KIPPster is going to go immediately to college, or necessarily ever to college. And I think that how this question gets answered is going to be part of the maturing of the charter movement.

I believe that we should hold out college-going as a powerful goal for our students, but it shouldn’t be the only goal, and we should both recognize that there will be some students who don’t have that as an aspiration or for whom immediately going on to college is going to have too many obstacles. So we have to give a lot more attention to career and understanding what does career advising and counseling and guidance tell us the opportunities are for our students.

The reality is that a high school diploma is, generally speaking, not going to be sufficient for 21st century careers that provide significant financial security, so there is going to be some post-secondary as well as career and lifelong learning requirements for all of us to be competitive in the 21st century. The charter community can be a really important thought partner with public education and the nation about what kinds of pre- and post-secondary educational and training opportunities can pipeline young people into meaningful and rewarding and choiceful careers throughout their lives.

If college is held as the golden standard in these schools, how do we control for the students who inadvertently feel like they’ve failed if they don’t go on to college?

Shaming is not an intended consequence of the heavy focus on college going, but it has been an unintended consequence, so we have to recognize that we don’t intend to shame our kids. I was at the KIPP school summit in Las Vegas. During the opening ceremony, the most powerful voice of a KIPP alum was of a young woman in her 20s who started college and dropped out, and after a lot of struggle has now found a powerful career and life direction as a champion for people with Lupus, and she’s one of them. And she’s doing it without a college degree, but she’s had a lot of training and opportunities in the meantime, and she’s reminded all of us at KIPP that every rule and every expectation is not necessarily the right rule and the right expectation for every student, so we have to think about this in a smart, thoughtful, and empathetic way as well.

I grew up in the 1950s in the public school system of Los Angeles, which tracked students based on race. And if you were black, brown, Asian, you were tracked into skilled labor programs, if you were white you were tracked into academic, and you had to literally claw your way out of the skilled labor system into the academic. We don’t want race, income, or zip code produce a 21st century tracking system, but we do have to recognize that immediate college after high school is not going to be in the cards for everyone. We’ve got to give them the tools, and we’ve got to champion their pathways if they choose more to follow a different pathway.

You’ve been at the helm of UNCF for more than 13 years. What has been your biggest accomplishment?

I think that at UNCF, there is not one thing that is more than the other. I think for me it is that we are founded as a social enterprise nearly 75 years ago that addressed what we thought was an important issue, and that’s helping African Americans achieve a college degree. We’re glad to see the rest of the country catching up with us in seeing that as a major national problem and opportunity.

For us, it is both doing our work with even greater passion and producing more scaled results that is also building collaborations with other like-minded organizations. And in the 21st century, one of those sets of organizations are high-performing public charter schools. I think together, UNCF and the high-performing public charter community can show the rest of the country what it takes to produce even more college graduates who can compete in the 21st century.

What does “success” mean to you?

As a parent and grandparent who’s thinking about success every day for the young people that are so close to me, it is giving them the kind of educational experiences that enable them to explore who they are, find out what their passions are, and to have the capabilities and the knowledge to pursue those.

There are always going to be obstacles and barriers, and some of those will only be addressed with external resources, but many of the barriers that we face as human beings are internal, so building the capability to achieve, to persist, to pursue, to resist those obstacles and to be resilient are very important, but also to create an environment externally, which gives our young people the supports and the resources that they need — oftentimes just enough to keep them on that journey toward their dreams. And that’s what I think of as success.

I don’t think of success as doing everything for somebody else, I don’t think of success as robbing them of their own sense of initiative and their strength to fight for what they believe in, but I also know that success isn’t achieved when you put too many huge obstacles in the way of young people. I think we, as a country, can do better, we are seeing evidence of what better looks like in high-performing charter and traditional schools, if we’ll just learn from that and scale it, we’ll see more success for young people.

Your Alumni

Story Here

We Recommend

-

Noble Network of Charter Schools: It’s Not Just About Going to College, It’s Also About Leaving to Learn Outside Chicago

-

King & Peiser: College Completion — Charter Schools as Laboratories

-

Gilchrist: My Charter School Saved My Life

-

Exclusive: Data Show Charter School Students Graduating From College at Three to Five Times National Average

-

WATCH: At Newark’s North Star Academy, 100% of the Class of 2017 Is Going to College

-

WATCH – The Alumni Tell Their Stories: College Gave Jadah Quick Upward Mobility

-

The Data Behind The Alumni: Unbundling Facts, Figures, and Caveats