Exclusive: Data Show Charter School Students Graduating From College at Three to Five Times National Average

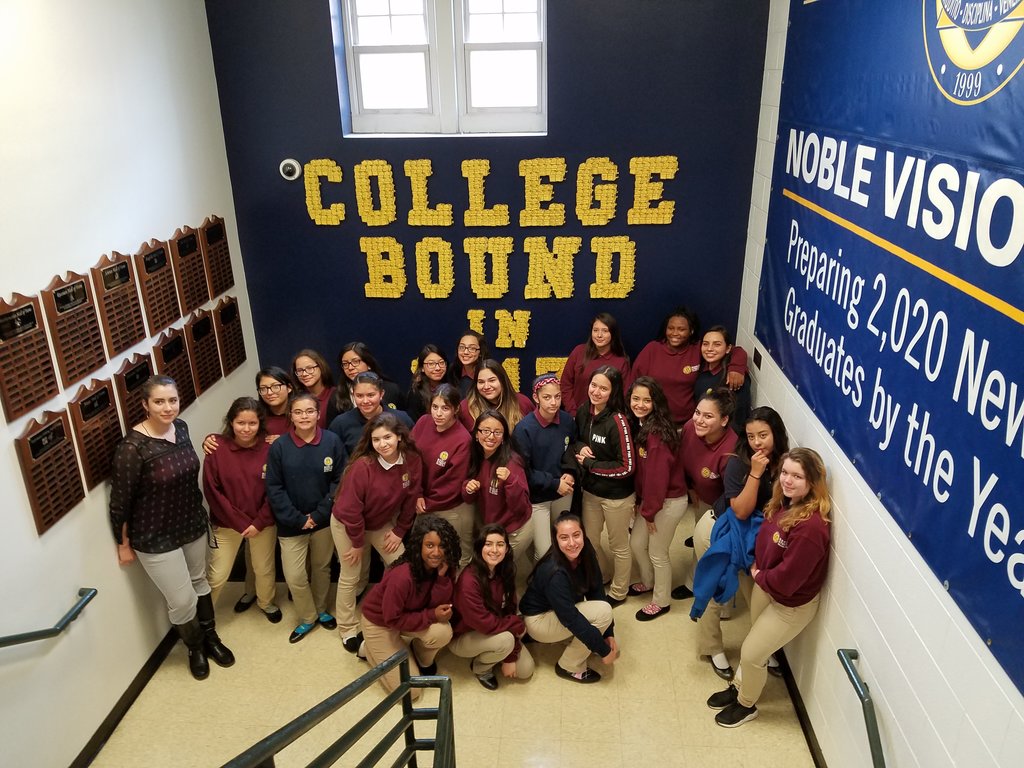

Noble Network’s college-bound seniors. (Photo credit: Richard Whitmire)

About a decade ago, 15 years into the public charter school movement, a few of the nation’s top charter networks quietly upped the ante on their own strategic goals. No longer was it sufficient to keep students “on track” to college. Nor was it enough to enroll 100 percent of your graduates in colleges.

What mattered, concluded the charter leaders, was getting your students through college — ensuring they earned a four-year bachelor’s degree within six years of graduating from high school.

Hold us accountable, the educators said, for how our kids do once they leave us, marking a remarkable paradigm shift in the way charter schools define success.

The initial spark may have happened in the 2008–09 school year, when KIPP realized its graduates were struggling in college. The network changed the name of its college success program from “KIPP To College” to “KIPP Through College” — a seemingly small tweak that signaled huge changes ahead.

Uncommon Schools was hearing similar feedback from its alumni, who faced financial challenges, struggled with being away from home, and felt uncomfortable at predominantly white colleges. Changes were required to ensure alumni not only gained access to college but actually earned degrees.

So Uncommon Schools moved in the same direction as KIPP, and other charter networks followed. The shift is yet another example of the intense sharing of best practices between America’s top charter networks, as documented in The Founders.

“You don’t just let family members leave home without helping them achieve their future goals.” —Richard Barth, CEO, KIPP

Today, the college graduation goal has been widely adopted, even by many single-site charters. At the small, relatively new Boston Prep, which serves students in grades 6-12, for example, classes are referred to not by the year students will graduate from high school, but the year they expect students to graduate from college. Next month, incoming sixth-graders will begin introducing themselves as the Class of 2028.

For several reasons, this dramatic strategic shift has drawn limited attention outside the charter school world, in part because to outsiders it seems to be a cross between brash and outlandish.

For starters, the proof of achieving the goal seemed nonexistent, at least at the time. Many charter networks were first launched only with elementary grades, and were too new to even conceptualize future alumni who could become college graduates.

Another reason the new goal has drawn so little attention is the common acceptance that students and the colleges they attend — not the students’ high schools, or even middle schools, in some cases — are responsible for whether those students earn college degrees.

But the charter networks are sticking to their new strategic goals, despite skepticism that high schools should be held responsible for whether their graduates earn college degrees. KIPP kids, CEO Richard Barth told me, are like family. You don’t just let family members leave home without helping them achieve their future goals.

At most, traditional high schools publish “college readiness” reports. In California, for example, parents can learn how many students at their local high school met the “A-G” course requirements required by the University of California system.

Many traditional high schools and private schools also grade themselves by calculating the number of their graduates accepted into colleges — but then rarely follow up to ensure that those students even enroll in their freshman year of college, let alone complete their studies to earn degrees.

Problem is, the traditional high school measures of college readiness are crude, as seen by the shockingly high number of incoming college freshmen who require remedial coursework before they are even allowed to take for-credit courses — a fault that leads to millions of degree-earning failures.

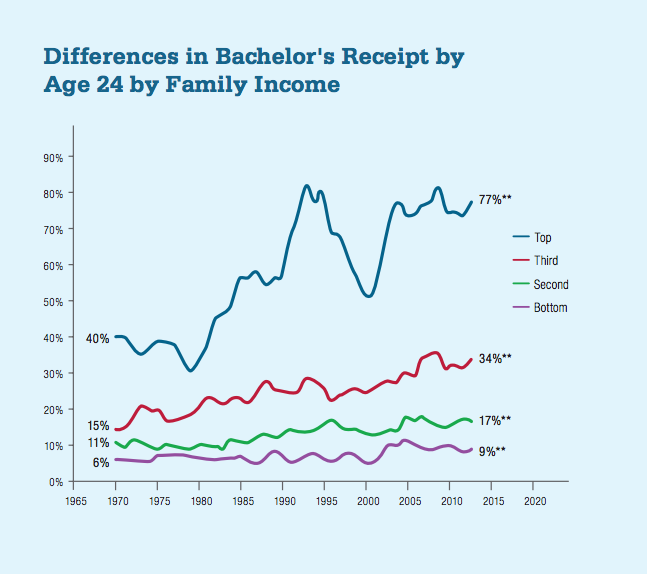

This makes the new goal set by the major charter school networks, to grade themselves on the percentage of their students who go on to earn four-year college degrees in six years, all the more radical — especially given the fact that these networks educate low-income, minority students, whose college graduation rates pale in comparison to their more affluent white peers — a mere 9 percent earning degrees within six years, compared with 77 percent of students from high-income families as of 2015.

If public and private high schools across the country catch on, this seemingly small ideological tweak in the charter sector has the potential to transform the entire American education system.

A LOFTY GOAL

Now, for the first time, it’s possible to start answering the question of whether that goal is achievable.

We identified nine large charter networks with enough alumni to roughly calculate degree-earning success rates. Chicago-based Noble Network of Charter Schools, for example, has more than 10,300 alumni, 1,444 of them past the six-year mark. Other networks have far fewer at the six-year point, but a sufficient number to measure meaningfully.

At this point in time, the quality of the data available for tracking their progress ranges from rough estimates to moderately precise, with the bulk coming from the non-government National Student Clearinghouse, which matches high school, college, and other identifier records to track students as they progress through higher education. The charter networks purchase the data from the Clearinghouse.

To account for imperfections in the Clearinghouse data, some charter networks also use internal tracking systems to ensure no student falls through the cracks. Others rely solely on the raw Clearinghouse numbers and don’t have systems in place to track on top of the Clearinghouse.

Another important notation about the data, which we explore in greater detail here, has to do with the denominator.

KIPP New Orleans (Photo credit: KIPP)

KIPP is a fervent believer that college graduation cohort data should be tracked from ninth grade — not 12th grade, the starting point that the other charter networks included in this study use.

For students who attend KIPP middle schools, KIPP tracks them when they graduate from eighth grade to ensure they are kept track of, regardless of whether they go to a KIPP high school.

For students who go to non-KIPP middle schools and start attending KIPP as high schoolers, they track them when they start ninth grade.

The problem with starting in 12th grade, argues KIPP, is that it could tempt schools to push out weaker students during high school years, thus allowing the stronger students to boost the schools’ college-going and college-completion rates.

KIPP may be right. But in The Alumni, where KIPP is the only network that is currently tracking students from ninth grade, we have decided it is important to share cohort graduation rates that start in 12th grade. What’s key to this series is learning what works in boosting that college graduation rate — lessons that could be passed along to all schools, not just charters. Moving everyone to the gold standard is the next step.

Below are the reported numbers of students who have earned a four-year college degree within six years of high school graduation.

For the one charter network that tracks students from ninth grade:

• KIPP Public Charter Schools: Across KIPP, a network of more than 200 schools with 80,000 students located in multiple states, 38 percent of the students who graduated from a KIPP middle school, or enrolled in a KIPP high school in ninth grade, are earning college degrees. (This number would certainly be higher — and closer to the rate at Achievement First and Uncommon — save for KIPP’s radical and model honesty policy of starting the graduation clock earlier to catch any high school dropouts.) In its New York region, profiled later in this series, the graduation success rate is 46 percent. KIPP uses both Clearinghouse numbers and its own tracking system.

For the eight charter networks that track students from the beginning of 12th grade, three compile their own data on top of Clearinghouse tracking:

• Uncommon Schools: For the New York–based network, the only alumni who have reached the six-year mark graduated from North Star Academy Charter School in Newark. (The alumni from its Brooklyn high school just reached the four-year mark. Of the 142 North Star students who reached the six-year mark, 71 earned four-year degrees: a 50 percent success rate. Based on factors such as rising GPA and SAT scores, Uncommon predicts a rising college success rate. For example, of the 80 students in the class of 2013, half graduated this June with a Bachelor’s degree, four years after leaving high school, and 23 percent are still enrolled in a four-year college. This fall Uncommon will have 570 alumni enrolled in four-year colleges; by 2020 Uncommon will serve 22,000 students in grades K-12 and have about 2,000 college-age high school graduates.) Uncommon uses both Clearinghouse numbers and its own tracking system.

• Achievement First: The network’s first two graduating classes to reach the six-year mark had only 25 and 19 students. For those students, the college graduation rate was 32 percent, a rate they say is poised to rise rapidly. But their subsequent classes, which have not yet graduated college, have far more students and thus can better represent the network’s success. Achievement First, which has schools located in New York, Connecticut, and Rhode Island, has 839 alumni, 314 of whom are upperclassmen who can be analyzed to project whether they will earn a diploma. Of those 314, 162 have earned at least 10 credits per semester, which is the primary indicator Achievement First is using to project a six-year college graduation rate of 52 percent. For its future classes of alumni, however, the network is forecasting college success with two additional criteria:

1. The student has been in college for at least six semesters

2. The student has at least a 2.3 GPA, and the most recent semester was at least a 2.3.

• YES Prep Public Schools: For this Houston-based charter network, 46.7 percent of the graduates earned a bachelor’s degree. That number is based on 569 graduates who reached the six-year mark, 266 of whom earned four-year degrees by then.

The remaining networks that track students from the beginning of 12th grade rely solely on Clearinghouse data:

• IDEA Public Schools: At this Texas-based network, which got its start in the high-poverty Rio Grande Valley, the rate is 35 percent.

• The Noble Network of Charter Schools: Among the many alumni of this Chicago-based network, the six-year degree-earning rate is 31 percent.

• Alliance College-Ready Public Schools: At this Los Angeles–based network, the rate is 25 percent.

• Aspire Public Schools: At this Oakland-based network, where the first graduating class was in 2005, the rate is also 25 percent.

One outlier:

• Green Dot Public Schools: This Los Angeles–based network will be included among the project profiles, but its graduation rate data are too cloudy to list here. For example, Green Dot says its “unmatched” Clearinghouse data are between 55 percent and 60 percent, which is unusually high. All the Green Dot graduation data will get discussed when the Alumni project profiles the network.

(The figures above raise numerous questions. Where do the numbers come from? How accurate are they? What about the dropouts? Why the big differences among the networks? For a more thorough discussion of the data, click here)

IDEA Public Schools seniors (Photo credit: IDEA Public Schools)

HOW THE FIGURES STACK UP

If you are a high-income white or Asian parent, these degree-earning rates will not impress. Among those parents, 79 percent of their children earn four-year degrees within six years after graduating from high school.

But because these charter networks almost exclusively educate low-income and minority students, the question has to be framed differently. The challenges faced by these students are incomparable to children from most upper-income families.

One quick example: In a 2017 internal survey of KIPP alumni currently in college, 43 percent said they had missed meals so they could have money for books, fees, and other expenses. Most alarming: 57 percent worried that food would run out before more money for food arrived.

So, let’s put these charter success rates in context. Among all students attending all types of schools in America, only about 9 percent of students from low-income families earn college degrees within six years. That means some of the top charter networks listed above, those in the 50 percent range, are doing five times as well.

Further, there’s tantalizing evidence in the college “persistence” data kept by these charters, where they monitor alumni still in college to determine if they are on track to earn diplomas, suggesting that bigger gains may be unfolding within a few years. Since the 2010–11 school year, for example, KIPP’s New York region was able to boost its six-year diploma-earning rate from 33 percent to 46 percent.

Individual charters that were early pioneers also have sufficient numbers of alumni to take a measure of their college success. Boston’s Academy of the Pacific Rim, for example, opened its doors in 1997 and now has 489 graduates since the class of 2003, its first graduating class, including 220 who have reached the six-year mark. Among those: 70 percent earned four-year degrees, the highest success rate we’ve come across in this project for a charter that targets low-income students.

If these rising success rates prove to be true, the civil rights and anti-poverty implications are significant. Is it possible to identify any anti-poverty program that has demonstrated effectiveness of this magnitude?

In the education field alone, consider Head Start, an early childhood education program that platoons of statisticians have argued about for decades, citing evidence of either small gains or no gains, depending on which study. What these charter networks are doing with college graduation goes far beyond scratching around for small-bore gains.

Celebrating graduation. (Photo credit: Alliance College-Ready Public Schools)

NEW PLAYERS ON THE FIELD

As part of this series, we profile most of the major players who have graduates past the six-year mark and describe their college preparation and tracking strategies.

Interestingly, the most compelling stories about improving college graduation rates may arise from the charter networks new to the push to make sure their graduates make it through college.

Los Angeles–based Alliance College-Ready Public Schools, for example, has a lower college success rate of 25 percent. That’s in part due to their rapid push into expanding the number of high school students they serve. They were also late to shift their focus toward tracking alumni in college, and they strive to limit additional spending on expensive guidance programs, for example, so they can offer themselves as a model that succeeds with low-income students relying on the same funding that goes to traditional public schools.

Can Alliance’s recent, low-cost method of using alumni and mentors boost their low degree-earning rates? That lesson may prove more valuable than lessons learned from KIPP’s more expensive college-tracking network, especially to traditional school districts unable to afford teams tracking their students into and through college.

If Alliance can make meaningful gains, then so could thousands of traditional school districts. And the same observation holds for what Green Dot, which started its college-tracking effort only two years ago.

KIPP students. (Photo credit: KIPP)

THE WORK OF PIONEERS

The charter networks profiled in this series are pioneers in this campaign — fulfilling one of their original charter school missions of becoming incubators of innovation. As such, their discoveries matter greatly.

Here’s a taste of what the front runners are learning: High school grade point averages matter far more than expected, and efforts to bolster GPA in high school give students the persistence skills needed to make it through college.

Another key lesson-learned: Like it or not, SAT scores matter a lot — not just in getting admitted, but also in persisting — which means pushing high school juniors into extensive preparation work for the test.

And the bottom line of every charter network: Research the hell out of which colleges work for their kids, and make sure they go there!

What readers are likely to find compelling about the charter networks profiled in this project are the different approaches used. KIPP, for example, throws its muscle into KIPP Through College, a hands-on campaign that tracks their students all the way through college.

At Uncommon Schools, the muscle focuses more on revamping and strengthening the academic program in grades 5–12 to give their graduates a tailwind through college.

Which works better? At the moment, both networks show roughly equal results.

There are some lessons that all the networks are discovering independently. Higher-ranked colleges do a far better job seeing their students through to a diploma. (In some cases, that range can be dramatic: 90-plus percent success at an elite college, compared with 15 percent or even lower at non-selective universities.) Thus, college counselors do their best to push students to apply for their “reach” schools.

Among the middle-ranked and lower-ranked universities, some do far better than others at ensuring that low-income students win degrees. So, all the charter networks employ aggressive counseling to keep their seniors away from the lesser-rated institutions. Noble network charters has a particularly interesting story there.

Another surprise finding: Many small but selective colleges that have traditionally enrolled nearly all-white student bodies, and are located in rural communities in states such as Pennsylvania and Ohio, are proving to be great collaborators with inner-city charters. Those colleges are seeing graduation rates above 90 percent with charter students. Who saw that coming?

To diversify their campuses, these colleges eagerly seek out well-prepared minority students (not just minority students from the middle and upper-middle class who went to suburban or private schools, but urban minority students truly in need of a boost) and are willing to take dramatic steps to ensure their success on their campuses.

The challenge for college counselors at these urban charters: getting their students equipped to survive far from home in an environment where few of their classmates share similar backgrounds as theirs: low-income minorities, some of whom are undocumented.

College signing day. (Photo credit: Uncommon Schools)

IT’S A REVOLUTION

While college-degree-earning rates may be important, the longer-lasting and still barely noticed development here is the declaration by the KIPPs, Uncommons, Achievement Firsts, YES Preps, and other networks across the country that earning college degrees should be the ultimate accountability measure for their high schools.

This is something new — and potentially revolutionary.

In years past, K-12 accountability measures focused on data points such as third-grade reading scores, the number of ninth-graders taking algebra, or setting new records for the most number of AP tests taken and passed. My prediction: Those data points will remain markers but will be subsumed by the far larger data point of college completion.

Like it or not, college is the new high school, regardless of the chosen career. Who doesn’t need to be a careful reader and writer to work in sophisticated blue-collar jobs? We need to judge high schools by how many of their graduates earn college degrees within six years.

And while charter leaders don’t want to stir up more controversy by saying it out loud, the implication is clear: Traditional high schools need to get on board with the same goal. Again, college is the new high school. And that rule applies equally to low-income minority students, who make up half the student bodies of our nation’s public schools.

Your Alumni

Story Here

We Recommend

-

Noble Network of Charter Schools: It’s Not Just About Going to College, It’s Also About Leaving to Learn Outside Chicago

-

King & Peiser: College Completion — Charter Schools as Laboratories

-

Q&A With UNCF CEO Michael Lomax: We’ve Got to Garner More Resources for Low-Income Kids for This Journey “To and Through” College

-

Gilchrist: My Charter School Saved My Life

-

WATCH: At Newark’s North Star Academy, 100% of the Class of 2017 Is Going to College

-

WATCH – The Alumni Tell Their Stories: College Gave Jadah Quick Upward Mobility

-

The Data Behind The Alumni: Unbundling Facts, Figures, and Caveats