Achievement First: Where Just Doing Better Than Its Peers Isn’t Enough, Network Sets Its Sights on Lofty 75% College Success Rate

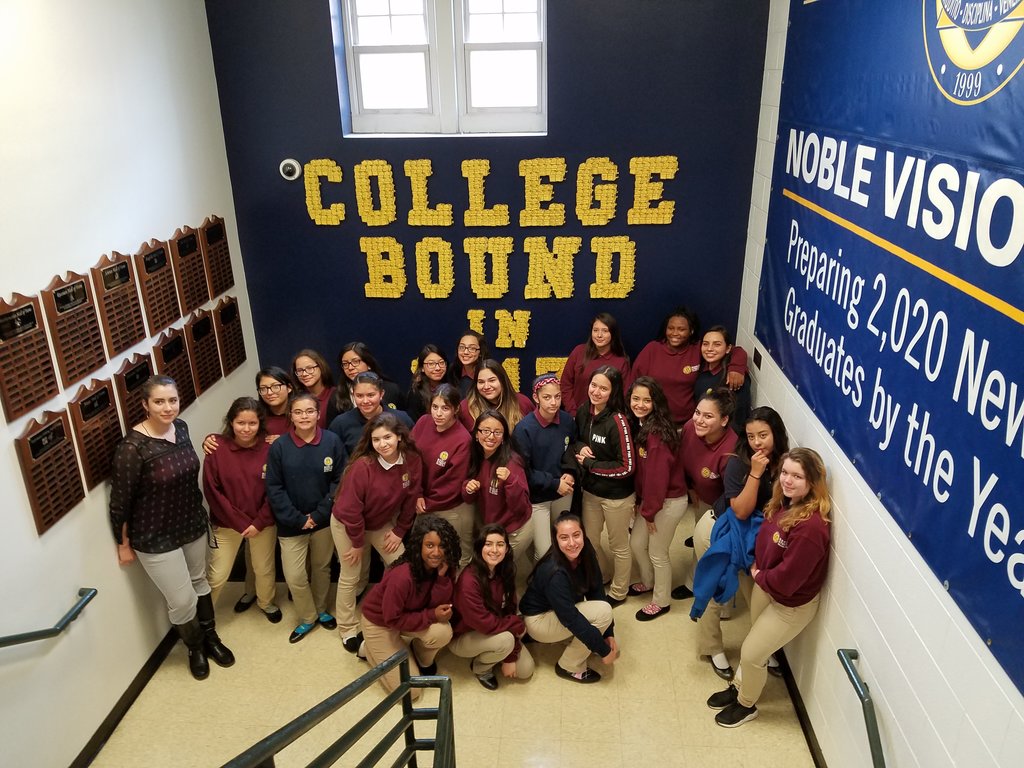

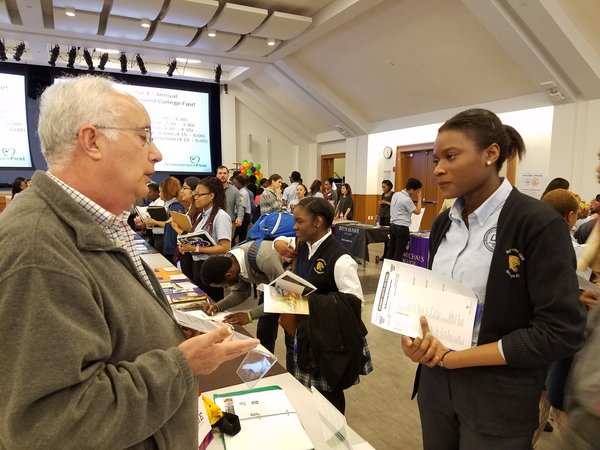

Achievement First senior Oluseyi Olaose talks to a representative from the University of Pennsylvania at a college fair in Brooklyn, N.Y., on April 20, 2017. (Photo Credit: Richard Whitmire)

At nearly 5 feet 11 inches tall, Nigerian-born Oluseyi Olaose is hard to miss in a crowded room. And even more so on one spring day this year in her school’s “cafetorium” because she’s wearing heels. Her statuesque presence and discerning disposition are undoubtedly making an impression on the University of Pennsylvania admissions representative at her school’s college fair.

“I’m really passionate about neuroscience,” she tells the representative assertively, and with complete eye contact. “I’m obsessed with the brain and how it literally controls every part of our body. But I’m aware that there are 11 percent women of color in the [science, technology, engineering, and math] field. Do you have any resources specifically for the sciences departments that will help me as a black woman who is interested in science?”

Olaose is a student well prepared by Achievement First college counselors for the task of engaging with college admissions representatives. Her dream acceptances are Ivy League colleges UPenn, located in Philadelphia, and Brown University in Providence, R.I., so being prepared is pretty much required.

This April 20 event marked the first-ever joint college fair held at the building shared by Achievement First — Olaose’s school — and Uncommon Schools in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood. There were 75 colleges represented, spread across tables in the huge room used both as a gym and cafeteria — a cafetorium.

What’s interesting about the gathering is its popularity among the colleges. The mostly top-ranked colleges present certainly aren’t looking for revenue; the low-income charter students at the high school, nearly all of whom would be the first in their families to graduate from college, would require almost full financial aid to attend those colleges.

Nor are the colleges looking for students “easy” to guide through graduation. These students require extra attention not just in academics but in adjusting to a completely foreign cultural ecosystem, and to being among the few students of color on their campus who grew up in some of the nation’s poorest neighborhoods.

THE REAL DEAL

In coming to charter schools such as Achievement First and Uncommon, the colleges know they’re getting the real deal. These are not minority students from the middle and upper-middle class who went to elite suburban high schools or private schools. These are the true faces of the future — the low-income minority students who now make up roughly half the nation’s K-12 student population.

And, best of all to these colleges, these charter schools have prepared their students to persist through the academic and social challenges that their campuses present. Thus the crowd of college recruiters.

There’s more at stake here than just a college fair. Playing out here is the ultimate accountability measure for charter schools. Can they justify the considerable disruption they have inflicted on traditional schools by guiding far more low-income minority students not just into college, but through college?

Here at Achievement First, one of the oldest “high-performing” charter networks, the answer appears an obvious “yes.” An estimated half of Achievement First students earn college degrees within six years — a rate three times (or as much as five times, depending on the measure used) that of similar students in Brooklyn neighborhoods such as Bedford-Stuyvesant.

‘GETTING STRONGER’

Since Achievement First shares this high school building with Uncommon Schools, there’s a fair amount of intermingling between the two staffs, which may explain why the two also share college success strategies, like a focus on grade point average.

To outsiders, GPA appears a squishy index. Critics argue that the averages depend on whether teachers are easy or hard graders, and a B in a rigorous class could matter more than an A in an easy class.

But what Achievement First and Uncommon have concluded is that the multitude of little skills that go into boosting GPA are the same skills needed for college success.

Here’s the evidence offered by Achievement First: Only 17 percent of its students with a GPA below 2.0 earn college degrees. Just a small boost to a 2.49 GPA vastly increases the college-degree-earning rate, to 62 percent. Achievement First students at the top, with a GPA between 3.5 and 4.0, earn college degrees at a rate of 92 percent.

Tracking students through college and stepping in when there’s trouble is another part of the formula. Nearly all students accept Achievement First College Book Scholarship money, $150 per semester, which helps offset cost for books and supplies with the condition that students turn over transcripts and participate in a survey. The program offers clues about how to tweak Achievement First’s K-12 courses to better prepare students to survive academically.

“We hope to raise our college graduation rate to 60 percent in the next three to five years,” said Adam Kendis, director of college access and success at Achievement First. Long term, the goal is 75 percent — a rate that matches students from high-income families.

Kendis is confident with the short-term 60 percent goal because “all our schools are getting stronger,” he said. “Each year we see graduates with stronger academic skills and habits. We have continued to refine our core academic model, which is Advanced Placement for all.”

There’s another reason: Achievement First conducted an internal analysis of the colleges selected by its most recent graduating class. Based on each college’s historical graduation rates for underrepresented minorities, Achievement First expects more than 60 percent of its class of 2017 to graduate .

Achievement First is about to launch a two-year course, called AP Seminar/AP Research, ”designed to give students an experience similar to what a college research paper is like.”

And, similar to other top charter networks, Achievement First seeks out college partners, of which the network currently has 10. Institutions like Union College in New York, Colby College in Maine, and Lafayette College, Franklin & Marshall College, and Susquehanna University in Pennsylvania agree to offer greater access, summer visit programs, and coordinated support systems for the Achievement First alumni.

Key to those supports, especially on rural campuses that enroll nearly all white students, are outreach efforts to students battling “stereotype threat” that makes them reluctant to seek help. Asking for help, Kendis said, often makes those students feel like failures.

All this makes a huge difference in graduation rates. At Lafayette, which was Achievement First’s first college partner, 90 percent of Achievement First alumni earn bachelor’s degrees.

Summer visit programs are the key to sending Achievement First graduates to nearly all-white colleges, said Amy Christie, a senior director at Achievement First who works with Kendis, focusing on K-12 preparation. “They see what it’s like to be the only student of color in a class.”

Both parents and students sometimes balk at leaving for isolated, mostly white campuses, both Christie and Kendis said. But it is colleges like Lafayette, Colby, and Franklin & Marshall that turn in the highest graduation rates for Achievement First alumni. Other colleges where nearly 100 percent of Achievement First students earn degrees include Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania and Bowdoin College and Bates College in Maine.

A SEARCH FOR INCLUSION

Olaose came to the United States nearly five years ago. Her father had a friend whose daughter was enrolled in an Achievement First school, which led Olaose to do the same. Olaose’s 4.0 GPA gives her lots of college options. To her, the array of colleges assembled in the school’s cafetorium resembled a tasty smorgasbord.

She stopped by the Kenyon College table to hear from Darci Kern, who not only is black but grew up in a gritty urban school district in St. Louis, graduated from Kenyon College in Ohio, and then taught Spanish in an Uncommon charter school for two years.

Kenyon leaders wanted a presence at the college fair for the same reason the other 74 colleges sent representatives. “We’re looking for really talented students who haven’t been able to get their foot in the door,” Kern said.

While she had a “tough transition” from urban St. Louis to rural Kenyon, located in Gambier, Ohio, Kern said Kenyon has since become far more diverse. “Kenyon has a lot to offer urban students,” she said.

Olaose seemed interested, but her primary targets remained Penn and Brown — especially Brown.

“I’m looking for a really inclusive college that will help me explore my identity in ways that I want, because my identity is so complex — just merging my experience as a black woman in America and as a Nigerian immigrant in the United States,” Olaose said. “It’s really, really hard to do.”

Your Alumni

Story Here

We Recommend

-

Noble Network of Charter Schools: It’s Not Just About Going to College, It’s Also About Leaving to Learn Outside Chicago

-

King & Peiser: College Completion — Charter Schools as Laboratories

-

Q&A With UNCF CEO Michael Lomax: We’ve Got to Garner More Resources for Low-Income Kids for This Journey “To and Through” College

-

Gilchrist: My Charter School Saved My Life

-

Exclusive: Data Show Charter School Students Graduating From College at Three to Five Times National Average

-

WATCH: At Newark’s North Star Academy, 100% of the Class of 2017 Is Going to College

-

WATCH – The Alumni Tell Their Stories: College Gave Jadah Quick Upward Mobility

-

The Data Behind The Alumni: Unbundling Facts, Figures, and Caveats