Green Dot Public Schools: Not Just About Getting Students Into College, But Getting Them Into the Right Ones and Keeping Them There

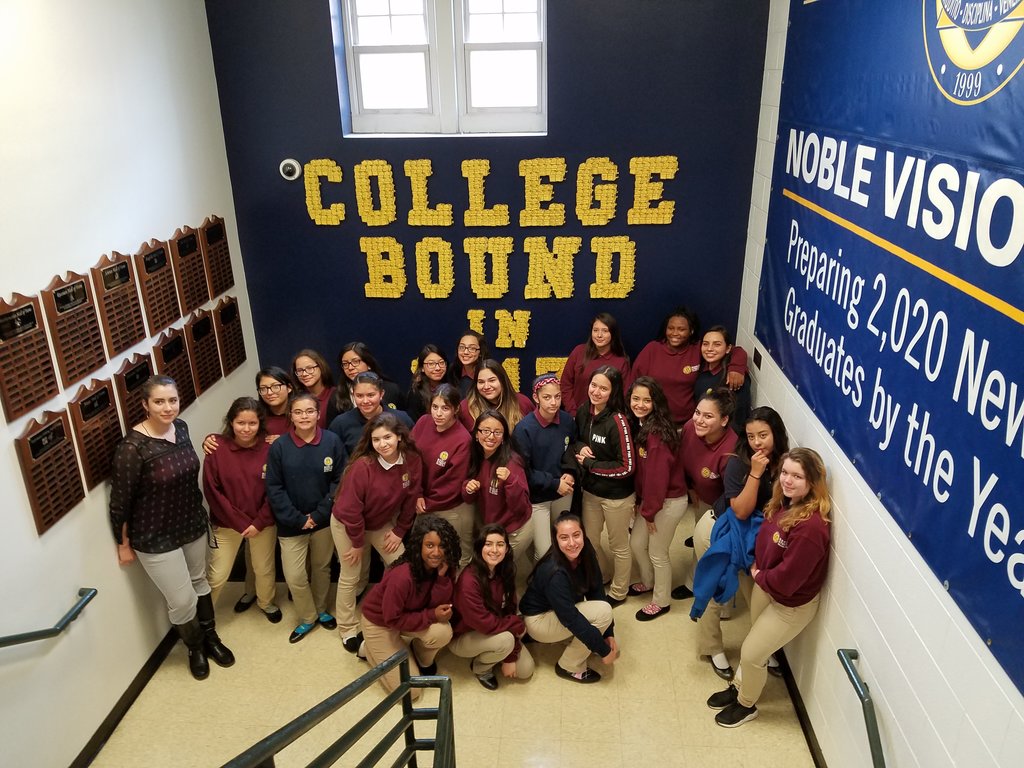

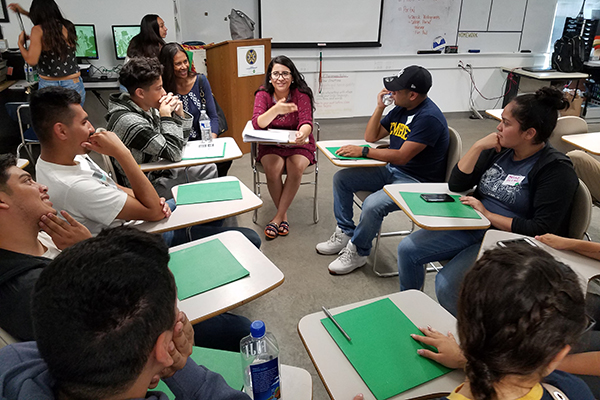

Green Dot counselors talk to students at a college prep gathering. (Photo credit: Richard Whitmire)

In an early-summer session for fresh Green Dot Public Schools graduates at Animo Leadership Charter High School Los Angeles, a college counselor asked for a show of hands: “How many of you are going to out-of-state colleges?”

Not a single hand went up.

There were a handful of students going to the University of California, Los Angeles, but most were headed to less selective California State University campuses, where they will probably work part-time — and are less likely to walk away with a degree. A fair number were headed to local community colleges, where the odds of eventually earning a bachelor’s degree hover in the scary range: Nearly three-quarters of those pursuing two-year degrees fail to earn those degrees or transfers to four-year institutions within six years.

That show of hands, or lack of hands, is one of several clues that explain why Green Dot is highly successful at getting all of its high-poverty graduates on a college track and admitted into college — but struggles to ensure they earn degrees.

According to National Student Clearinghouse data shared by the network, only 16 percent of Green Dot graduates earn bachelor’s degrees within six years. Green Dot says the figure is low because of Clearinghouse’s low rate of matching their records with college records. Roughly translated, that means the Clearinghouse couldn’t find their alumni.

For the class of 2004, for example, the match rate was only 55 percent, according to Green Dot. For comparison: at Texas-based IDEA Public Schools, which educates similar kinds of students, the match rate is about 94 percent. Students at Chicago’s Noble Network of Charter Schools match at a rate of about 90 percent.

If Green Dot based its success rate only on the students successfully tracked, the success rates rises to 34 percent, according to the network’s internal calculations.

Green Dot is still investigating the cause for the low match rates. One suspect: a high percentage of its students may be claiming privacy exceptions — “FERPA blocks” (Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act) that keep their college records private, making it impossible for the Clearinghouse to track them.

That was on display in Los Angeles during my visit as counselors remarked on the number of students clicking “yes” on the box enabling the privacy block as they worked online to update their college portal.

Who wants to share their higher education records — especially in a time when the federal government is ratcheting up its pursuit of undocumented immigrants? Green Dot, by state law, does not keep records on the immigration status of its students and their parents. But based on my interviews with students at Animo Leadership and Animo Inglewood Charter High School, the number of undocumented, especially parents, appears to be high.

There are multiple reasons for placing Green Dot in a separate category when evaluating college success rates, at least for now. One reason is that Green Dot takes chances that few charter networks do. In the 2008-09 school year, Green Dot took over the famously dysfunctional Locke High School in L.A.’s Watts neighborhood. The school, where perhaps 5 percent or less went on to earn college degrees, was built after the riots there in the 1960s. (That estimate comes from the principal when Green Dot took over, Green Dot founder Steve Barr said).

Absorbing Locke nearly doubled Green Dot’s enrollment. Some of the Locke students barely had contact with Green Dot before they graduated — a significant factor in the network’s college success rate.

Overall, Green Dot serves a student population that is about a quarter black and three-quarters Latino. Its student body is also composed of those with backgrounds that tend to be among the most challenged: 91 percent qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, 25 percent are English language learners, and 12 percent have special needs.

But those demographics don’t seem any more challenging than the students who enroll in IDEA schools in the Rio Grande Valley, where the college success rate is considerably higher. Nor can taking over Locke explain all of Green Dot’s modest college success rate.

At Animo Leadership, a school so close to LAX that outdoor conversations are difficult when planes are landing (which is pretty much all the time), the college success rate is only 18 percent. Calculated with a denominator of students “found” by Clearinghouse, the success rate rises to 25 percent.

Green Dot is not claiming it has a high college success rate. The network started its alumni tracking-and-support efforts only about two years ago, said Janneth Johnson, head of counseling and college persistence. And the effort is just getting up to speed.

Green Dot’s Janneth Johnson, director of counseling and college persistence. (Photo credit: Richard Whitmire)

So far, Green Dot’s college success efforts appear modest compared to other charter networks part of this project, especially the college guidance staffing. College counselor Reyna Casanova, who works at Green Dot’s Animo Inglewood school, is one of only two counselors at a school with more than 600 students in grades 9-12. And her duties include far more than college counseling.

“We do it all, the scheduling, the college component, the mental health component, the social and personal,” Casanova said.

That’s a sharp contrast to my visit to KIPP NYC College Prep, where both college counseling teams and KIPP Through College teams appeared capable of flooding the zone.

Green Dot says it can’t be compared to the East Coast charters, which have far higher per-student spending. It’s true that California has relatively low student reimbursement rates – almost half of what some charters in New York City receive, depending on where they are located. But the per-student reimbursement here is almost exactly the same as the reimbursement in Texas, where IDEA’s college success rate is higher. The elaborate KIPP Through College program operates off independent fund raising.

What the Green Dot high schools have are “alumni champions,” in which teachers are paid stipends to take on a caseload of graduated seniors and act as a resource for alumni who struggle with academic, social, or financial issues in college.

Before that program, graduating seniors essentially disappeared every June, Casanova said.

“I’d bump into a graduate at the mall and say, ‘Hey, aren’t you supposed to be at UC Santa Cruz?’ and she would answer: ‘Um, I’m not going there anymore,’” Casanova said.

But the alumni champion, one per campus, only carries a caseload of only 25 students, which leaves the rest of the graduating class mostly untracked. At some universities, such as UCLA, Green Dot hires alumni as “university mentors” to assist incoming students.

Part of the difference between Green Dot and other charter networks, Johnson said, is that Green Dot embeds its college counseling into regular classroom instruction, with teachers becoming college advisers. But the challenge at Green Dot appears to be less about counseling students on getting accepted into a college than getting them into the right colleges, and then keeping them there until they earn degrees.

IDENTIFYING THE LEAK

There are multiple leaks: shaky financial aid, family pressure to work and stay in Los Angeles, students unready for college academic work, and students making ill-fated choices about where to go to college.

“A lot of times I‘ve had kids that get into great schools outside California,” Casanova said. “For example, this year I had a girl get into Mount Holyoke College. Great financial package. But her parents refused to let her go, even though it was the best fit for her.”

This phenomenon, also experienced by counselors at all-Latino charters like IDEA, is unfathomable to upper-income white and Asian parents. Who doesn’t accept an invitation to go the best college possible? But it’s very real in neighborhoods such as Lenox and Inglewood, home to the students coming to this college-prep session.

At schools like Mount Holyoke, more than 90 percent of first-generation students end up winning diplomas. Instead, Casanova said, the student ended up locally, at California State University L.A., a university where just 19 percent of the freshmen end up with diplomas after six years.

More worrisome is the high number of Green Dot alumni headed to local community colleges (Green Dot puts that number at about a third), where for these students, the odds of eventually winning a four-year degree are in the single-digit range.

“Some kids get into four-year colleges but choose to go to community college because it’s cheaper, or they can work and help their families,” Casanova said.

Other students, Casanova said, rationalize their way into making poor college decisions. “They might say, ‘I didn’t get into UCLA, my dream school, so I’m just going to go to El Camino [College, a nearby community college] and then transfer to UCLA.’”

Except that transfer rarely happens.

A few years ago, Casanova was more tolerant of decisions like that. “I felt like I had to respect their decisions,” she said. But that attitude has changed.

“Now I feel like I have to advocate, which means telling them the harsh truth, that they’re going to be at El Camino for four, five or six years, just like the other kids,” Casanova said.

Compared to a traditional high school, especially in the many high-poverty neighborhoods of Los Angeles, Green Dot does an admirable job tracking its graduates once in college. But when compared to the charter networks reporting college success rates in the 50 percent range, Green Dot has ground to make up.

Regardless, Green Dot’s modest college success rate appears to easily exceed that of Los Angeles Unified School District and other local districts where Green Dot students would have ended up had they not gotten a low number via the charter school lottery.

YARITZA GONZALEZ

One of the alumni who attended an early-summer session as an alumni mentor was Yaritza Gonzalez, born and raised in California. She first lived in Oxnard, where both her parents picked strawberries, and then moved to Inglewood, where her parents now work as restaurant servers.

Gonzalez and her parents signed up for the Green Dot lottery, and all showed up for the draw. Yaritza’s name was the third called out. That was a great relief for her parents, because the schools she had attended through middle school worried them. “I almost cried, because it meant so much to my parents.”

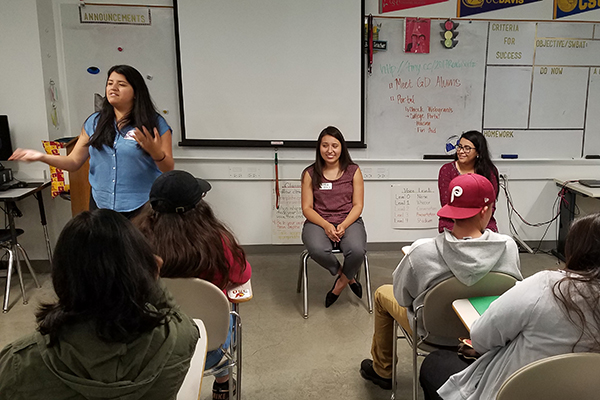

Green Dot counselor Reyna Casanova (left) with alumni Yaritza Gonzalez (center) and Gabriela Figueroa (right) as they talk to fresh graduates. (Photo credit: Richard Whitmire)

If Gonzalez had not won a seat at Green Dot, she would have attended Morningside High School, part of Inglewood Unified School District, only a block from her home in Inglewood. Today, with the benefit of hindsight, she realizes how lucky she was, and why her parents were so happy. Many of her girlfriends from middle school got pregnant and dropped out. Several of the boys she knew are dead, victims of gang violence.

Gonzalez comes from a close-knit family that emphasizes education, so she assumes she would have survived Morningside and most likely ended up at one of the nearby California State University campuses, universities with modest college success rates.

Instead, she graduated as a Green Dot salutatorian and won a full scholarship to Dartmouth College, from which she has graduated. On this day, she offered advice to just-graduated Green Dot seniors.

It was fascinating to watch her interactions with the students. The cliché “pin dropped” applies: These soon-to-be college freshmen hung on every soft-spoken word. Her advice: Reach out for help. Don’t be afraid to ask for extensions, for personal help from professors, for more financial aid.

“If you are honest about your experience,” she said, referring to growing up in Inglewood, “then people are more willing to help you.”

Later, Gonzalez said that out-of-state colleges often offered better chances of graduating, but there are challenges. At Dartmouth she entered a world where nearly all the students were wealthy and white — many the sons and daughters of Dartmouth alumni.

“It’s intimidating at first,” she said. “Everyone else seems to know what they are doing.”

She described the stunned silence among her privileged Dartmouth classmates in get-to-know-you sessions as she described her upbringing. They weren’t being mean, they just had no way of relating. Better to say nothing than something inappropriate.

The pull of family obligations also leads to diploma-earning challenges.

“Family issues really stick with you when you are far away,” Gonzalez said, especially for the oldest child in the family like her. “You feel this need to come back and solve the problems.”

The biggest challenge is avoiding falling into insularity, she said, failing to build community, failing to ask for help.

“Many [first-generation] students are intimidated to ask a professor for help or an extension,” Gonzalez said. “We feel like we’re being judged, that it would show we’re not prepared, that we can’t handle the rigor.”

Green Dot alumna Gabriela Figueroa talks to recently graduated seniors. (Photo credit: Richard Whitmire)

LEARNING FROM GREEN DOT

While Green Dot may not be “killing it” like Uncommon Schools and Achievement First, where success rates are as much as five times the general like-student population, their college success rate, even if it’s only roughly double that of LAUSD (estimate only — LAUSD doesn’t have official college success data), has to be viewed as a modest success.

One way of looking at Green Dot is to view it in the same light as Alliance College-Ready Public Schools, also based in Los Angeles. In both cases, the push to improve college graduation rates are recent, affordable and doable — programs that traditional school districts and charters lacking deep pockets could emulate.

Green Dot’s college persistence campaign is new, and the network seems candid about the need to improve.

“We are not afraid of the data,” Johnson said.

Your Alumni

Story Here

We Recommend

-

Noble Network of Charter Schools: It’s Not Just About Going to College, It’s Also About Leaving to Learn Outside Chicago

-

King & Peiser: College Completion — Charter Schools as Laboratories

-

Q&A With UNCF CEO Michael Lomax: We’ve Got to Garner More Resources for Low-Income Kids for This Journey “To and Through” College

-

Gilchrist: My Charter School Saved My Life

-

Exclusive: Data Show Charter School Students Graduating From College at Three to Five Times National Average

-

WATCH: At Newark’s North Star Academy, 100% of the Class of 2017 Is Going to College

-

WATCH – The Alumni Tell Their Stories: College Gave Jadah Quick Upward Mobility

-

The Data Behind The Alumni: Unbundling Facts, Figures, and Caveats