Noble Network of Charter Schools: It’s Not Just About Going to College, It’s Also About Leaving to Learn Outside Chicago

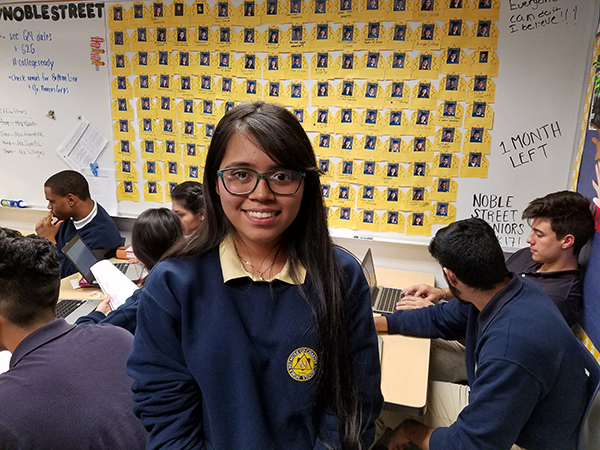

Noble senior Michelle Alvarez. (Photo Credit: Richard Whitmire)

The Noble Network of Charter Schools in Chicago is huge: 17 high schools serving 11,000 students, with 10,345 alumni. And, it has history, at least by charter school standards: Noble’s first school, Noble Street College Prep, was founded by Michael and Tonya Milkie in 1999.

(Watch Michael Milkie discuss Noble as part of The 74’s project, The Founders.)

That breadth and longevity make Noble a valuable research asset in looking at charter school college graduation rates. To date, 31 percent of its graduates have earned college degrees within six years (35 percent if the deadline is pushed beyond six years).

Considering that nearly 80 percent of the children raised in high-income families (the top 25 percent) earn college degrees within six years, that figure of 31 percent seems less than impressive. But Noble’s student body is 98 percent minority and 89 percent low-income — a group where, nationally, only 9 percent earn degrees within that time frame.

WHAT 31 PERCENT MEANS

Noble’s rate is at least double that of Chicago Public Schools generally, and probably far more than double the comparable rate for similar low-income minority students within CPS.

The best comparison comes from research out of the University of Chicago. Across CPS, the six-year college graduation rate for Hispanic students is 11 percent for males and 16 percent for females; Black students graduate within six years at a rate of 6 percent for males and 11 percent for females. The current graduating class at Noble is 44 percent black and 54 percent Hispanic.

Ask Matt Niksch, Noble’s chief college officer, whether 31 percent is a “good” rate, and he answers, “I’m not comfortable with how well our alumni are doing. Most of our efforts now are focused on getting them into the best colleges possible. We’ve gotten better. Also, we’re working to better prepare kids for college.”

Niksch may be right about that. In the past two years, the degree-earning rate for Noble students at the six-year mark jumped to 54 percent, which may point to an improved rate that will persist.

GETTING OUT OF CHICAGO

It’s May 4 on Noble Street College Prep, Noble’s flagship campus, and there are two sessions of a college seminar class. The program is key to guiding students into colleges where they will come away with degrees. Seniors file into the 11:04 a.m. class, pop open their laptops, and pull up their college websites — their portals to a new life.

May is a time when seniors already know where they’re headed in the fall for college, so it has the feel of a victory lap: All that’s left is mopping up the last details about financial aid packages, housing applications, work-study jobs… and fantasizing about their new, exotic lives as college students.

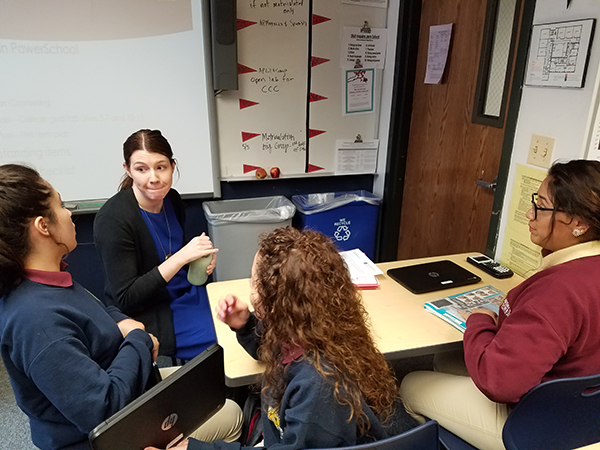

In one corner, Erin Greenfield, dean of college at Noble Street College Prep, sits with four girls headed off to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Their questions for Erin: Is it better to room with someone you know? Somebody brand-new? Am I going to get a refrigerator in my room? A microwave? Do we need to go grocery shopping?

Greenfield explains that no, there’s no need for shopping. All their meals will come via the college dining halls.

For Greenfield, these are fun questions. The hard part for her is done, especially with these four girls. Landing a spot at the University of Illinois’s main campus is huge: Nearly 80 percent of the Noble students who get accepted there earn degrees within six years.

Erin Greenfield, Noble Street dean of college, talks with students. (Photo Credit: Richard Whitmire)

This year, Noble will send about 270 students to the flagship campus. That success rate varies greatly by campus, however. At the University of Illinois at Chicago campus, for example, only about half of Noble’s alumni earn degrees within six years.

For Greenfield, improving the college success rate is all about landing students in the right spots. Her job is challenging in ways that a college counselor at a suburban high school or private school likely can’t even imagine: About a quarter of the parents at Noble Street College Prep are undocumented, and between 5 percent and 10 percent of the students are undocumented.

Undocumented parents are often reluctant to see their kids leave Chicago, a sanctuary city. For starters, it most likely means they fear taking their children to college, or visiting them, or even attending their graduation. It also often means they will lose the one member of the family with a driver’s license, the one member of the family they count on for running errands. Thus the pull to keep their sons and daughters in Chicago.

For undocumented students, it means financial aid becomes extremely difficult. Yet another undertow that might keep them from leaving Chicago.

Thus the challenge for Greenfield, who usually wants to get her students out of Chicago, away from commuter colleges where college success is limited, and into colleges where financial aid covers nearly all expenses.

Greenfield knows what every college counselor I interviewed knows: the more selective the university, the more likely it is the student will earn a degree.

Ideally, all the students in this class would land in places such as Northwestern University, where 90 percent of the minority undergraduate students will earn degrees within six years. But that’s not realistic. The real challenge is finding the right spot for her students who have B or C-plus grade point averages.

Greenfield and her staff know precisely where she doesn’t want to see those students end up: places such as Northeastern Illinois University, where only 15 percent of Noble-like students end up with degrees, and Chicago State University, where only 20 percent of low-income minority students earn degrees within six years.

The attraction for students to places like Northeastern is clear: cost, convenience, a chance to live close to home, and the opportunity to both work and study. Many of those “advantages,” at least as seen by students, are exactly the factors why so few end up walking away with degrees.

Greenfield and her staff have worked hard to steer their students away from universities like Northeastern, and they are making progress. In prior years, 10 to 12 of their seniors ended up there; this year only four did.

“When we sit down with parents we’re very sure to mention this is the graduation rate [at Northeastern], and we show them alternatives,” Greenfield said.

Fortunately, Noble has alternatives: National Louis University and Arrupe College of Loyola University Chicago, where the Noble counseling staff estimates the graduation rate will be at least 40 percent. Arrupe is a two-year college designed to guide first-generation college students into a successful path to earn a four-year degree.

For the higher-performing Noble students, Greenfield and her staff recommend smaller colleges, often in the Midwest — colleges eager to recruit well-prepared minority students who can diversify their campuses. Just a few: The College of Wooster and Oberlin College in Ohio, Carlton College in Minnesota, Albion College in Michigan, Holy Cross College in Indiana, and Gettysburg College and Lafayette College in Pennsylvania.

“They want our students because ultimately they want to educate everybody, not just the rich,” Greenfield said. “I think colleges are looking to diversify for the world. They know the need for a diverse perspective in their classrooms, and our students can help provide that.”

These colleges come to charter networks such as Noble also because the students come with supports, Greenfield said. If Noble alumni struggle in college, the Noble staff in Chicago is available to help them. This is one of the ironies of The Alumni project: The colleges most successful with charter school graduates — largely low-income minorities — are those with a history of enrolling student bodies that are almost entirely white and middle-class. For the counseling staff at the charter schools, the big challenge is getting their students mentally prepared to survive, and thrive, on rural campuses where most of the students will look nothing like them and will share none of their growing-up experiences.

Often, the biggest resistance comes from parents, who don’t want to see their children leave for relatively obscure locations for four years of college.

One of Noble’s programs, Summer of a Lifetime, addresses that challenge directly. Noble students apply to do a summer college program, where before their junior year they spend up to three weeks on a college campus.

“It almost always goes well,” Greenfield said. “They have a good experience, they come back safe, they come back eager, and their parents have that initial touch of what it would feel like for a longer term.”

ANTHONY RODAS: NEARLY A FULL RIDE TO YALE

Anthony Rodas, whose parents came to the U.S. from Guatemala when they were teenagers, is headed to Yale University in the fall. He also got offers from Princeton and Brown universities. Rodas grew up speaking mostly Spanish. His mother has always worked as a nanny; his father works at a company that makes windows.

Yale is offering Rodas $63,000 in scholarships to offset a full college bill of about $66,000. The remaining $3,000 balance is up to Rodas to meet with work-study jobs on campus. Just to be safe, he’s planning to wait a semester before taking a job.

Noble senior Anthony Rodas. (Photo Credit: Richard Whitmire)

“Transitioning from an inner-city school like Noble will be a different experience compared to the kid who’s coming in from one of the top boarding schools in the country,” Rodas said. “I need to acclimate to the environment at Yale and make sure I’m on top of my academics.”

To Rodas, the transition from a Hispanic neighborhood in Chicago to Yale looks intimidating.

“At Noble I’m used to performing really well and I’m at the top of my class, so it’s really scary because I know that’s not going to be the case at Yale,” he said.

Rodas plans to major in political science, with aspirations to become a lawyer, with a specialty in immigration law.

ROBERTO: GETTING OUT OF THE GANG NEIGHBORHOOD

For Roberto, whose name has been changed to protect his identity, both his parents were born in Mexico and came to the United States when they were young. His mother stays at home and his father works in construction.

Life changed for his family after Donald Trump’s election.

“My parents are a lot more worried about going out and sometimes it makes me worried too,” Roberto said. “I worry about my dad going to work. I’m scared that if the cops pulled him over he would get sent back to Mexico. He’s the one supporting us now, with everything we need.”

The family relies on Roberto to do the chores that involve driving, which is one reason his parents preferred that he stay in Chicago for college. But Roberto wanted to leave Chicago, and he’s headed to the University of Dubuque in Iowa, about a three-hour drive away. He aspires to be a nurse.

Roberto chose Dubuque because that was one of the schools he visited on a field trip to see colleges, and because he felt the campus was welcoming.

One reason he wanted to leave the city was the crime in his neighborhood, especially gang activity.

“It worries me because my little brothers are always outside playing around,” he said. “I worry they could be at the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Roberto realizes he will be in a minority at the university, but that doesn’t bother him.

“I’m really outgoing and I make friends easily,” he said. “I’ve never been the victim of racist comments and stuff like that.”

STEPHANIE SARABIA: HEADED TO UPENN, ‘I GOT HERE FOR A REASON’

Stephanie Sarabia was born and raised in Chicago and is headed to the University of Pennsylvania.

Her parents, who are from Mexico, own a business in Chicago, Tony’s Burrito Mex. Sarabia waitresses there on occasion. She ended up at Noble because her older sister is a Noble alumna.

At Penn, Sarabia plans to double major in English and international relations.

“They have the Penn in Washington program, and that’s one of my focuses, as a guide into the political world and foreign world,” Sarabia said. “I’ve been attracted to the United Nations, and followed what they have done.”

Noble senior Stephanie Sarabia. (Photo Credit: Richard Whitmire)

Despite her academic success at Noble, earning a 4.2 GPA, she remains worried about life at Penn.

“The fact that they are an Ivy League school, I know it’s going to be rigorous and I’m going to be challenged,” Sarabia said. “I think sometimes no matter how smart you are or how great your grades are you still have that self-doubt: Can I actually do this? Will I be able to succeed?”

Those worries, Sarabia tells herself, are a way to keep her grounded.

“I’ll be telling myself: I can do this,” she said. “I got here for a reason.”

Your Alumni

Story Here

We Recommend

-

King & Peiser: College Completion — Charter Schools as Laboratories

-

Q&A With UNCF CEO Michael Lomax: We’ve Got to Garner More Resources for Low-Income Kids for This Journey “To and Through” College

-

Gilchrist: My Charter School Saved My Life

-

Exclusive: Data Show Charter School Students Graduating From College at Three to Five Times National Average

-

WATCH: At Newark’s North Star Academy, 100% of the Class of 2017 Is Going to College

-

WATCH – The Alumni Tell Their Stories: College Gave Jadah Quick Upward Mobility

-

The Data Behind The Alumni: Unbundling Facts, Figures, and Caveats