Shalvey: Dramatic Support for Educators Rather Than Political Drama

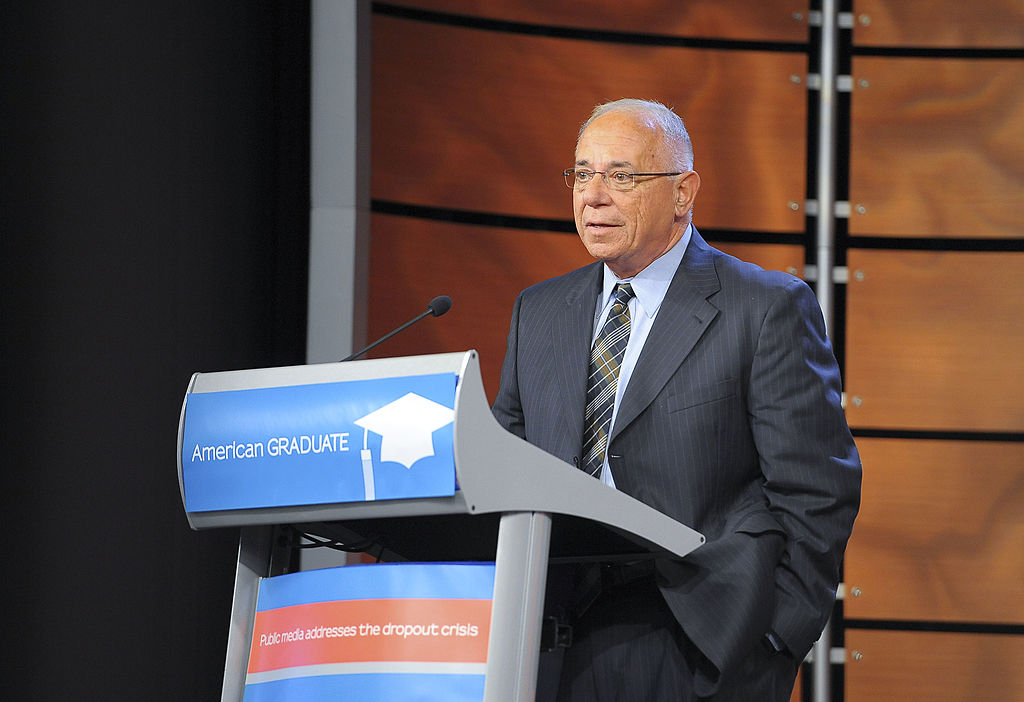

Don Shalvey attends the Education Initiative discussion at the NEWSEUM on May 3, 2011 in Washington, D.C. (Photo Credit: Leigh Vogel/Getty Images)

We live in a time of inflamed rhetoric, in which it somehow seems permissible to denigrate people who may not share our views without ever actually listening to them.

Particularly when it comes to public schools, I’m hoping we might listen a little more and shout a little less.

All of us, even those of us who are truly accomplished educators, have a lot to learn. There certainly are plenty of students who need our collective help in their own learning.

I just celebrated 50 years as an educator. That is perhaps enough experience to have a bit of perspective.

I started as a teacher in the summer of 1967 — the Summer of Love, as it was called.

I’d traveled from my hometown of Philadelphia to a small farming town in central California to teach middle school. One Saturday morning, I entered my classroom to start getting my room in shape for the seventh-graders I was going to inspire to be mathematicians.

On my transistor radio I listened to Procol Harum’s “Whiter Shade of Pale” and The Doors’ “Light My Fire” and tried to figure out the ersatz air conditioner — a swamp cooler — in the window. The radio played the Beatles’ “All You Need Is Love.”

But sitting in my classroom, alone on that Saturday, figuring out how and when I should turn on the cooler and just what those bulletin boards should look like, I realized that Lennon and McCartney lied to me. I needed far more than love. I needed help, wisdom, experience, and more answers than I could imagine, and, I hadn’t even met my students yet.

Throughout the next quarter-century I continued to be a committed and inspired public school educator. To me, teaching is one of the most noble and dignifying of professions. It is also lonely and vexing, and every educator longs to be better for their students. Not once in my career did I ever believe that any teacher, principal, or superintendent started their morning thinking, “How can I ruin my students today?”

But I often thought that teaching is too private and too devoid of serving as a learning institution for the very adults that long to better serve the young people in their care.

My experience is that learning from colleagues matters. It made me better to talk with those middle school math teachers who’ve unlocked ways to help their students solve problems like,

As a salesperson, you are paid $50 per week plus $3 per sale. This week you want your pay to be at least $100. Write an inequality for the number of sales you need to make, and describe the solutions.

I didn’t care if that teacher taught at our rival middle school in the district or at the Catholic school down the street. It’s about me getting better for my students. I love and respect my colleagues who shared their successes, failures, and quandaries. “Secret sauce” may work for In-N-Out Burger, but not for public education.

A quarter-century later, it’s 1991 and I’m now a school district superintendent in Silicon Valley. I read that California’s governor has signed a charter school bill to allow for 100 schools that had the opportunity to “encourage the use of different and innovative teaching” and/or “create new professional opportunities for teachers, including the opportunity to be responsible for the learning program at the school site.”

So my community — the parents, the Board of Education, our teachers and civic leaders — got behind the San Carlos Charter Learning Center. It was the first charter school in California and the second in the nation. We didn’t do it to create competition or to embarrass the other schools in the district or area. We did it because we needed to get better at integrating technology in the classroom and find better ways to implement multi-age instruction. It was a concrete symbol that schools have to be purposeful learning organizations that advance the capacities of both the students and the staff.

As one of the earliest founders in the charter public schools sector I want to be clear: Our work was about innovating and committing to learning and sharing what we learned with teachers and principals everywhere. It was not about crushing the competition, as some critics are wont to say.

Today, another quarter-century has passed and some people fan the flames of charter-schools-versus-district-schools drama rather than dramatic support for teachers and principals. I suggest we embrace the latter. Let’s leave crushing the competition to the National Football League and not act like it’s the reason educators create and work in charter public schools.

That’s why I delight in KIPP’s college completion initiative and the hundreds of traditional high school counselors who are learning alongside the KIPP team. And the same goes for Summit Prep’s Learning Program and the 3,000-plus teachers (both district and charter school teachers learning side by side) who came to learn.

Let’s celebrate similar efforts like STRIVE Prep’s relentless pursuit to improve support to students with disabilities, because we know that every teacher who has a student with an Individualized Education Program longs for more tools and techniques.

Then there’s Achievement First’s principal preparation program that includes aspiring district and charter leaders and Success Academy’s summer program attended by more than 900 educators.

For me, that is the point. Fifty years past The Doors and The Monkees keeping me company in my classroom, teachers still seek to get better. And they don’t care if their learning comes from a teacher in a charter school or a neighborhood public school. It’s about getting better.

So, at the start of the 2017 school year, let’s celebrate those schools, charter and district, that commit to learn with and for one another — students and adults alike.

Don Shalvey has been a teacher, principal, school district superintendent, and co-founder of Aspire Public Schools. He is now deputy director at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, where he leads investments in charter schools, teacher and leader preparation programs, and tools for school management and operation. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation supports The 74.

Your Alumni

Story Here

We Recommend

-

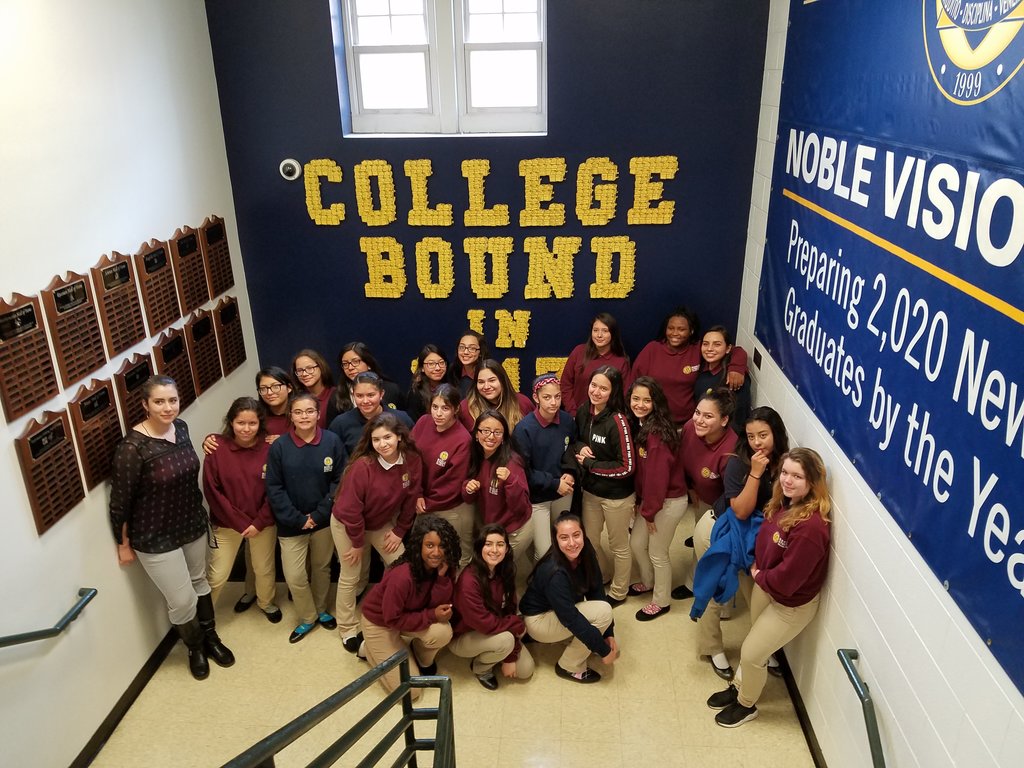

Noble Network of Charter Schools: It’s Not Just About Going to College, It’s Also About Leaving to Learn Outside Chicago

-

King & Peiser: College Completion — Charter Schools as Laboratories

-

Q&A With UNCF CEO Michael Lomax: We’ve Got to Garner More Resources for Low-Income Kids for This Journey “To and Through” College

-

Gilchrist: My Charter School Saved My Life

-

Exclusive: Data Show Charter School Students Graduating From College at Three to Five Times National Average

-

WATCH: At Newark’s North Star Academy, 100% of the Class of 2017 Is Going to College

-

WATCH – The Alumni Tell Their Stories: College Gave Jadah Quick Upward Mobility

-

The Data Behind The Alumni: Unbundling Facts, Figures, and Caveats