YES Prep: At the Birthplace of College Signing Day, ‘Pumping Out Kids Prepared and Ready to Roll’

YES Prep college counselors gathered for an interview in spring 2017. (Photo credit: Richard Whitmire)

Visit any of the big charter networks in the spring and you might catch a raucous “signing day,” where seniors brandishing college banners proudly and loudly shout out to an arena full of friends, family, teachers and classmates: “I’m going to ___ college!”

That all started in Houston, Texas, in 2000. On a chilly October night that year, YES Prep founder Chris Barbic and his college counselor and neighbor, Donald Kamentz, stopped by Ernie’s on Banks, a bar in the Montrose neighborhood started by a Chicago guy who loved Cubs star Ernie Banks — so he decided to open a joint on Banks Street.

Barbic and Kamentz were sipping Shiner Bocks, munching on Tombstone pizzas (it was the only food the now-shuttered bar served) and watching ESPN’s SportsCenter, which was broadcasting college signing day for the nation’s top student athletes. Lots of drama, lots of shouting, lots of happy families.

“Why shouldn’t our families experience the same acclaim?” they reasoned. Most are the first in their families to go to college, many of them headed to name-brand universities. This needs celebration.

“Our kids were going to declare their own colleges and nobody was going to make a big deal of it,” Kamentz said. “What if we made a big deal of it?”

Thus was born the senior signing day, in June 2001, with the first 17 graduating seniors of YES Prep and their families, who were cheered on by about 300 younger YES Preppers and the staff. They all fit into a small theater at an adjoining community center. It was a hit, and each year it grew and was replicated by other charter networks.

These days, YES, which now has 17 schools educating 12,600 students, holds its signing ceremony in Houston’s massive Toyota Center, where the Houston Rockets play.

But that’s just the beginning of the college success strategies invented at YES Prep.

Today, most charter networks build college partnerships, in which the colleges recruit their students, give them full financial rides — or close to it — and promise to recruit their students in small “clusters” so they won’t be isolated. In short, they promise to go the extra mile to ensure they graduate.

That, too, started in Houston in 2006 with YES Prep via partnerships called IMPACT. The origins were conversations with an admissions representative from Iowa’s Grinnell College who knew Kamentz from Teach for America.

“We love your kids, and we know from the Posse Foundation program that recruiting students in clusters works,” the representative said. “Why not draw up a recruitment deal that helps both YES and Grinnell?”

That first year, Grinnell was the only IMPACT partner. The program has since grown to about 35 partners today. YES Prep may not be the biggest charter network in the country, but when it comes to pioneering college success, it’s the clear leader.

IMPACT TODAY

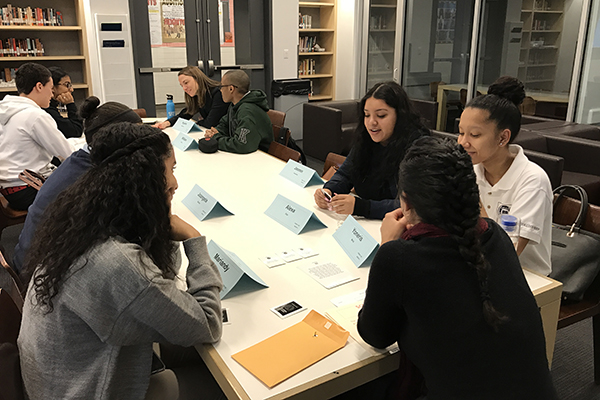

Those college success rituals were on full display on an early August day this year — several weeks before Hurricane Harvey tore through Houston — during an IMPACT gathering, where college representatives set up interview tables and conducted small group sessions. A sample of the colleges represented: George Washington University, Grinnell College, Hamilton College, Bucknell University, Johns Hopkins University, and Kenyon College.

These are colleges willing to meet the full financial needs of YES Prep students and admit students in “clusters” to help reduce student isolation. On this day, the IMPACT college representatives had one pitch for the YES Prep seniors: “Apply to our school!”

One more interesting thing about this IMPACT gathering: Parents are invited, and they participate fully. Pushing up college graduation rates often requires getting parents to agree to send their sons and daughters out of state, and among these mostly Latino families that’s not always an accepted practice.

IMPACT launched before most charter networks even started focusing on college success. At that point, their long-term goal was limited to college admittance. Barbic and Kamentz recognized that the real push had to be college completion and saw an opportunity: Colleges wanted to diversify, and charters like YES Prep could offer them the well-prepared students they were looking for. In exchange, the colleges would agree to meeting their financial needs and supporting them once on campus.

“Our job was to pump out kids prepared and ready to roll,” said Barbic.

The students invited to this day’s IMPACT session represent YES Prep’s top 25 percent. Most have grade point averages of at least 3.4, good SAT scores, and an impressive record taking Advanced Placement courses in their junior year, and are continuing to take AP classes now in their senior year.

Colleges fight for these students. They are academically prepared and represent the nation’s diverse future: 85 percent Latino and 13 percent black. About 85 percent come from low-income families.

YES Prep’s early start in focusing on college completion probably explains its high college graduation success rate: 46.7 percent earn four-year degrees at the six-year mark. While that falls well short of what high-income families experience (80 percent), it’s a remarkable rate given its student population. Only 9 percent of the children from families in the lowest-earning quartile earn degrees.

One reason for that 46.7 percent figure is the very high success rate for the students entering IMPACT colleges. Among these top YES Prep students, 84 percent have graduated from or are still enrolled in their original IMPACT college.

And YES Prep college counselors deal with challenges that college counselors at a typical suburban high school can’t even imagine: Laura Villafranca, the counselor from YES Prep’s Gulfton campus, estimates that a third of her students are Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals beneficiaries, and more than half of their parents are undocumented. That demographic representation is unlikely to describe a suburban traditional public school.

Here’s what that means when pursuing college success. For starters, a lot of your graduates won’t even consider out-of-state colleges, even though many of those colleges have great college completion rates. First, because DACA students in Texas can get in-state tuition. These YES Prep students can’t get loans to go to out-of-state colleges, so just take that entire option off the table.

Second, undocumented parents don’t want to their children go to college anywhere other than local. Even going beyond Houston is considered dicey.

“The parents are afraid,” Villafranca said — afraid of the risk of deportation if they leave their communities. Why send your children to a college where you will never be able to drop them off for their freshman year, and are not likely to attend their graduation?

Yet another issue that most college counselors might not tend to deal with, and one that might strike outsiders as odd: The counselors at YES Prep say they have to work hard to convince their students that they are “minorities” who may feel isolated on distant college campuses:

“I’ll say, ‘You’re a minority,’ Villafranca said. “And they will say, ‘No, I’m not.’ They will look left, and right, and they look at the hallways and everyone there speaks Spanish. They look at me and say they don’t know what I’m talking about. So I tell them when they step foot on this [new college] campus and look around, they may be the only student of color or one of a handful of Latinos. Everyone is going to look at you … What’s your response going to be when an entire class turns and looks at you and says, ‘Tell us about the Hispanic experience?’”

Veteran counselor Peter Olympia said YES Prep pours all its resources into academics. Many of their students arrive at YES schools in sixth grade reading at the second- or third-grade level. YES probably does a better job bolstering academics than it does preparing its students for the dramatic social challenges they will face in college, he said.

The best antidote there, Villafranca said, is bringing in alumni who have gone to colleges known as PWI — Predominately White Institutions. Those are the voices that current high schoolers will listen to.

Even the simplest things, like explaining the expenses of a plane ticket to their new institution, or buying clothes to attend a college in cold-weather climates like Massachusetts, New York, or Vermont, can take a lot of explaining and effort.

“This is very much a sit-down conversation,” Villafranca said. “I’ll tell them, ‘You’re going to the University of Rochester. You have no idea how cold it is. You need to buy a winter coat.’ And they will look at me and say, ‘But I have a sweatshirt; I’ll just layer.’”

Yet another challenge: Nowhere in Houston can you buy a winter coat suitable to survive at New York’s University of Rochester.

And even if the students think they can come up with round-trip airfare, Villafranca has to warn them about the expenses of making multiple trips during the school year.

“The conversation we have with the family is they should try to identify a friend on campus because they probably won’t be coming home for Thanksgiving, or they won’t be coming home for spring break,” she said.

All the counselors in the IMPACT group session agreed that hidden fees — charges not covered by students’ nearly full-ride scholarships — were among their biggest challenges. The biggest ones are housing deposits that they thought were waived but are actually deferred and being required to pay for campus health insurance if they aren’t covered by parents. That health insurance bill can run from $1,500 to $3,000 a year.

Another surprise cost: having to pay to attend college orientation. That can run $300 to $500. And some colleges schedule orientations in June or July, which means having to come up with airfare for a separate trip.

In general, expenses that run $3,000 to $5,000 over the offered scholarship are considered no-gos, by both the parents and the college advisers.

STUDENTS TELL THEIR STORIES

Destinie York, 17, entered YES Prep in seventh grade, a move that her mother engineered.

“She didn’t want me to go to a high school where people would fight me,” York said. “She wanted me at a school where people cared about me.”

YES Prep student Destinie York (Photo credit: Richard Whitmire)

Destinie’s mother, who graduated from college, works as a bookkeeper at a Walgreen’s; her father works in vending.

In her junior year, York took AP English and AP physics.

“Physics was really hard. I cried almost every night,” she said. In her junior year, she is taking three AP classes, including calculus.

With a GPA of 3.5 and good SAT scores, York is hoping to land a spot at Rice University, which was one of the universities represented during the IMPACT gathering.

“If Rice gave me a scholarship I would go.”

…………

Axel Palapa, 17, aspires to graduate from Columbia University in New York City with an engineering degree. His mother and a sibling live in Mexico. He lives in Houston with his aunt, uncle, and two cousins.

YES Prep student Axel Palapa. (Photo credit: Richard Whitmire)

Palapa came to YES five years ago, transferring from another charter school that he thought was less academically demanding.

In his junior year, he took three AP classes — French, physics, and English literature — all while working 30 hours a week as a cashier at Taco Bell.

In his current senior year he is taking another three AP courses, including calculus. His GPA: 3.98.

Palapa has never been to New York City; the closest he came was taking a summer course at Cornell University in upstate New York for budding minority engineers. Cornell, he said, was too rural. He’s convinced that he’s a natural New Yorker.

“I want an urban setting,” he said. “New York City is where I see myself in the future.”

…………….

Elysia Garza, 17, has been at YES Prep since sixth grade. Entering the YES admissions lottery was her idea.

“My father didn’t want me to go to YES,” Garza said. “He thought I was going to be stripped of my childhood and have no fun at all.”

YES Prep student Elysia Garza. (Photo credit: Richard Whitmire)

Garza has no regrets about her decision, citing a college visit trip she was able to make to Washington, D.C., where she visited George Washington University and Catholic University, as well as Goucher College and Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Without YES’s support, that trip would not have happened, she said, and without the IMPACT program, Garza feels she would have stood no chance of getting a full financial ride from any of those institutions.

Her first choice: George Washington University, where she wants to study international affairs.

“I loved the political climate there, and everyone was welcoming,” Garza said. “I also liked how fast-paced it was.”

A representative from George Washington University was on campus that day. To go there, Garza would need a full scholarship.

“I come from a very low-income family,” she said.

Your Alumni

Story Here

We Recommend

-

Noble Network of Charter Schools: It’s Not Just About Going to College, It’s Also About Leaving to Learn Outside Chicago

-

King & Peiser: College Completion — Charter Schools as Laboratories

-

Q&A With UNCF CEO Michael Lomax: We’ve Got to Garner More Resources for Low-Income Kids for This Journey “To and Through” College

-

Gilchrist: My Charter School Saved My Life

-

Exclusive: Data Show Charter School Students Graduating From College at Three to Five Times National Average

-

WATCH: At Newark’s North Star Academy, 100% of the Class of 2017 Is Going to College

-

WATCH – The Alumni Tell Their Stories: College Gave Jadah Quick Upward Mobility

-

The Data Behind The Alumni: Unbundling Facts, Figures, and Caveats